The Real Treasure of the Valley of the Kings

The spectacular royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings were intended to be the final resting place of the pharaohs of the New Kingdom and their (often golden) possessions. One of the smallest tombs in the valley, yet far and above the most famous, is the tomb of Tutankhamun, whose nine year reign was a footnote to history before the treasures of his burial were splashed across newspapers across the world (this, despite how interesting and significant events occurred during his short rule). As I will argue here, the greatest treasure of the Valley of the Kings is not Tutankhamun’s gold, but the hieroglyphic texts and associated images that decorate the walls of the royal tombs.

Today, the best known funerary text from ancient Egypt is the Book of the Dead. Although this composition is one of the few to have a surviving title, it is rarely used: The Book of Going Forth By Day. The chapters (or spells—the ancient Egyptian word is just “speech, utterance”) empowered a person’s soul—royal or non-royal—to travel out of his or her tomb with the sun god, thus going forth each day. And “book” is not accurate, either—scribes wrote these texts on papyrus scrolls, for the codex, the origin of a book with pages between covers, is not common before the fourth century CE. For the sake of concision, I will use book here also to mean a textual and pictorial composition transmitted on papyri.

Only a few walls in the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings include the Book of Going Forth By Day, with thousands of square feet dedicated to another group of texts that Egyptologists call the “Underworld Books” or “Netherworld Books.” The latter name acknowledges that the realm through which the sun god travels at night can be located beneath the earth or in the body of Nut, divine personification of the sky. One must not interpret ancient Egyptian theology as logical series of either-or scenarios—the gods and the Netherworld are beyond human comprehension, and thus, they do not conform to physical laws (unless the Egyptian Underworld mimics Schrödinger's cat).

The Netherworld Books are not personal manuals for reaching the Field of Reeds and spending a blessed eternity with Osiris. These books are texts and images that describe the journey of Re through the twelve hours of the night, compositions of cosmic significance. The knowledge contained within the Netherworld Books is knowledge of how the world itself works. The mysteries within these books are so powerful, so dangerous, that only a select few, including the king and upper echelons of priests, could study and use them.

Inside the tomb of Seti I, with the king embraced by Isis (column, foreground) and a portion of the Fifth Hour of the Book of Gates above the staircase.

The six compositions that make up the Netherworld Books appear first within the royal tombs of Valley of the Kings and a small number of non-royal tombs of the New Kingdom. The texts continued to be used in the first millennium BCE, with a renascence in the Nectanebid Period (Thirtieth Dynasty, 380-343 BCE). Four books appear to survive in full: the Litany of Re, the Book of Amduat, and Book of Gates, and the Book of Caverns. Large portions of the two other compositions, the Book of the Creation of the Solar Disk and the Books of the Solar-Osirian Unity are extant, but additional sections may await further discovery.

Over five-hundred pages is needed to translate this massive corpus—as demonstrated in the only complete, English translation, by John Coleman Darnell and myself: The Ancient Egyptian Netherworld Books. The space that these books occupy on royal tomb walls are most often evenly split between images and hieroglyphic text. Except for longer passages of hymns, the texts are essentially captions to the scenes—what Re does and says, the actions of the thousands of Netherworldy gods, and the complex geography of the Netherworld.

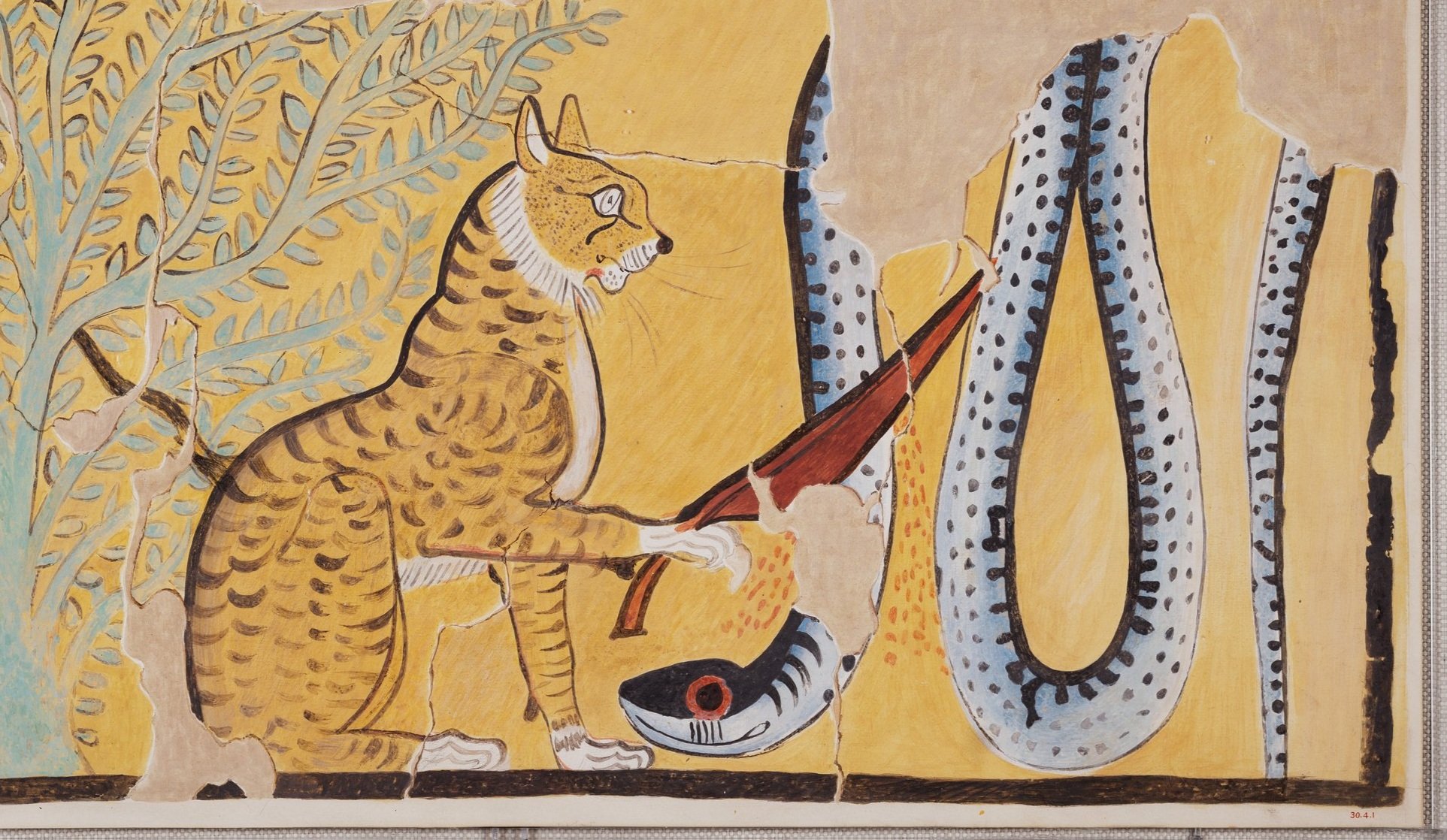

In upcoming blog posts, I will explore these books in greater detail, but the theme that unites them all is Re’s successful navigation through the Netherworld. The sun’s triumphant rise from the eastern horizon is the template for the resurrection of all blessed dead (and cats and dogs!). Apep, a giant serpent who embodies chaos and destruction, poses the greatest threat to Re.

Burial chamber in the tomb of Ramesses VI with his fragmentary sarcophagus and scenes from the Book of the Creation of the Solar Disk.

The Book of Amduat describes one version of the nightly battle in the Seventh Hour (the ancient Egyptians divided each solar day into twelve hours of day and twelve hours of night, meaning that the length of an hour differed throughout the year). As Re speaks effective magic spells, Isis and the Elder Magician perform their own magic to defeat Apep. The Elder Magician is a personification of heka, the ancient Egyptian word for magic and a natural force that both gods and mankind can harness (more to come on that fascinating topic as well).

The walls of New Kingdom tombs, and some later papyri and sarcophagi, preserve knowledge of ancient Egyptian theology found nowhere else in such rich detail. Without them, we would understand much less of ancient Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife and the solar cycle, and we would lack some of the greatest religious literature of the ancient world. The Netherworld Books may not glitter, but they are cultural gold.

Further Reading

John Coleman Darnell and Colleen Manassa Darnell, The Ancient Egyptian Netherworld Books, Writings from the Ancient World 39 (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2018).

Joshua Roberson, “The Rebirth of the Sun, Mortuary Art and Architecture in the Royal Tombs of New Kingdom Egypt,” Expedition 50:2 (2008): 14-25.