The Secret Language of the Baboons

In the temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, the right, rear portion of the temple has a roofless room for the worship of the sun god. The decoration within the solar chapel includes one scene from the Book of the Night, which appears on the ceilings of some Ramesside Period tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Other texts and images in the Medinet Habu shrine are closely related to the Netherworld Books and express many of the same themes that I summarized in an earlier post.

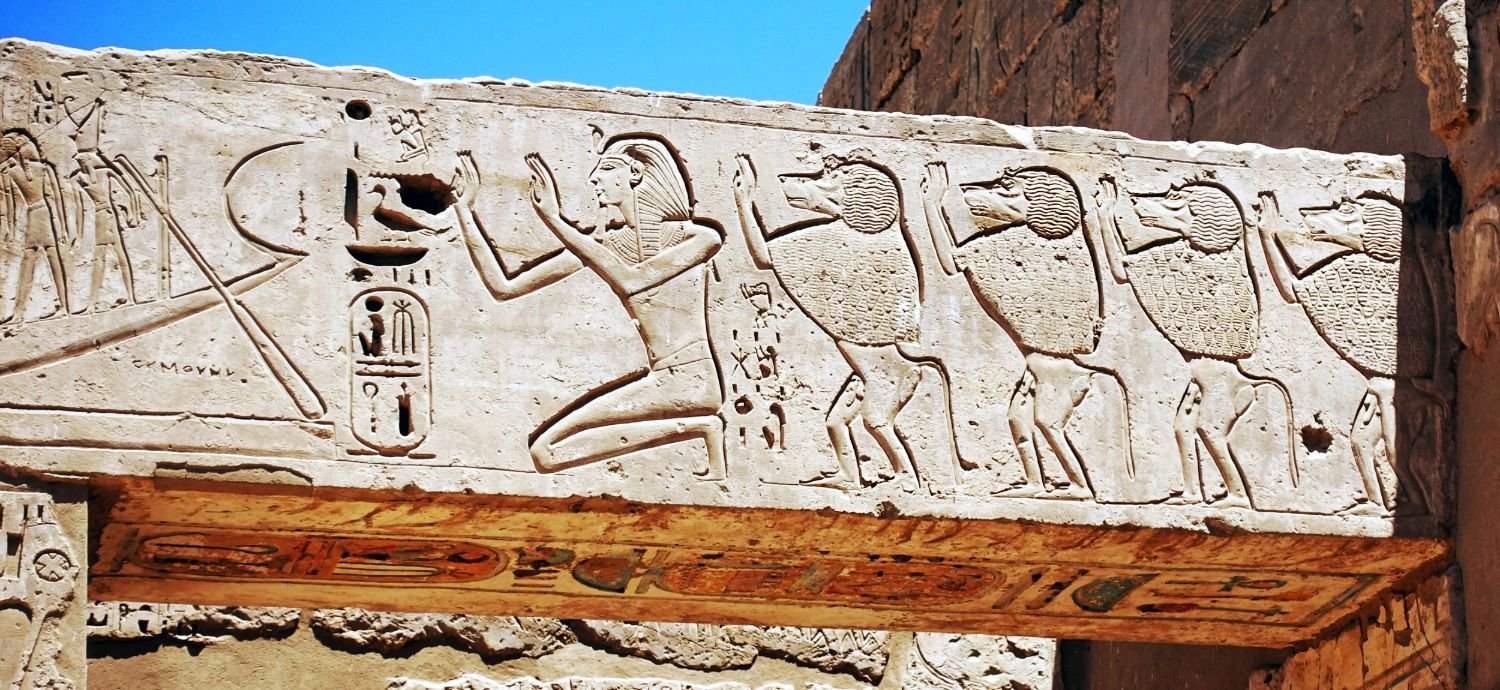

A lintel within the solar chapel has a image of Ramesses III kneeling in praise before Re. Four baboons accompany the king and adopt the same posture. In front of the king, the hieroglyphs read: dw3 rꜥ in s3 rꜥ nb ḫꜥ.w Rꜥ-ms-sw ḥq3 iwnw “Adoring Re by the son of Re, lord of glorious appearances, Ramesses, ruler of Heliopolis.”

The verb dua (dw3), “to adore,” is written with a single sign, an image of the king kneeling with his arms raised in a praising gesture. The hieroglyph is exactly the same as the image it labels, and the sign both writes the word dua phonetically and depicts the action. The use of a hieroglyph as a direct represention of a word is called a logogram or ideogram.

The sun disk in front of the king is also a logogram—it writes re (rꜥ), the name of the sun god, and depicts the manifestation of the deity visible each day. The stroke beneath the sun disk marks the sign as a logogram. In the ancient Egyptian language, word order dictates that a verb is placed before its subject. Yet in the lintel, the signs are intentionally reversed.

The solar chapel in the temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu (photo by C. Darnell)

The hieroglyphs are read dua re, but the change in order means that the signs show the king worshipping the sun god. This is a perfect illustration of how hieroglyphs both write the sounds of the ancient Egyptian language and can simultaneously embody things in the world. Outside of tombs and temples, such uses of hieroglyphs are rare—the vast majority of written texts are straightforward and lack such playful symbolism.

The caption to the baboons behind the king writes “The baboons who adore Re.” The first sign, a baboon in the same posture of praise as the animals it labels is again a logogram. Normally, a baboon hieroglyph would be seated, but again, the sign are specifically tailored for the context. The three strokes below the baboon makes the noun plural—“baboons.”

The lintel of the solar chapel, showing the king and baboons praising the bark of Re (photo by C. Darnell)

Then the star and praising man write the same very dua, “to adore,” that was written with the praising king sign in his caption. The star here is a purely phonetic sign representing the three sounds d-u-a (dw3--technically, the last sign is an aleph, which does not have a corresponding letter in English, so is conventionally written a, although a short a sound is very different from an aleph—more on this when we dive deeper into hieroglyphs).

In the baboon caption, the verb dua follows the noun, because the verb is a participle, “who praise.” Participles function grammatically as adjectives, which follow nouns and agree with the noun in number, hence the repetition of the plural strokes. The last word of the caption is Re (rꜥ), spelled with the sun disk, stroke, and seated god. The god sign is a determinative, a sign that does not have phonetic or logographic value, but rather serves as a classifying sign. Re is a god, thus he is classified with a hieroglyph depicting a seated god.

These short hieroglyphic texts demonstrate the three uses of hieroglyphic signs (phonogram, logogram, and determinative) as well as the flexibility of spelling, sign forms, and ability to create symbolic juxtapositions.

Detail of the lintel in the solar chapel (photo by C. Darnell)

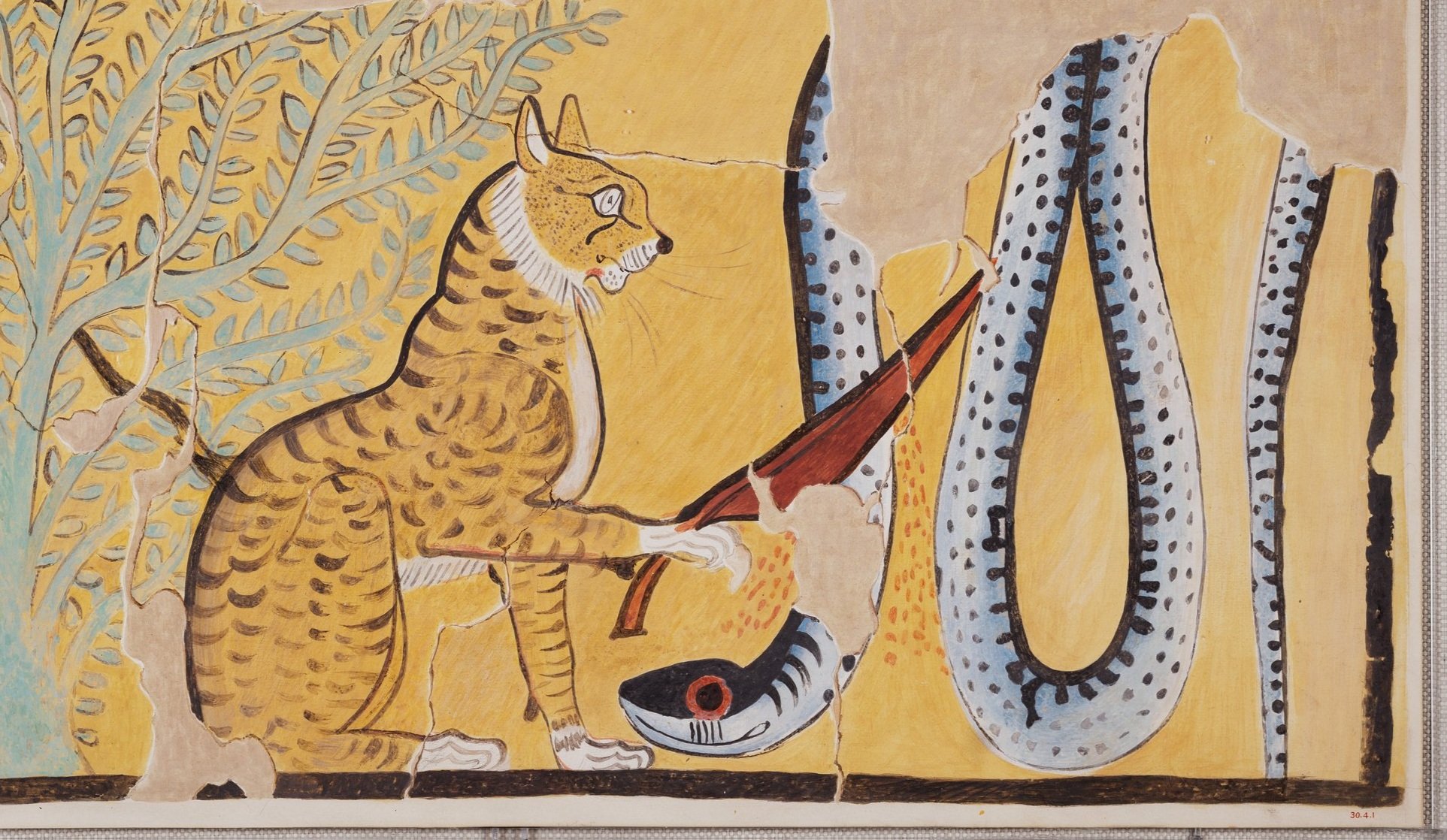

Having read the hieroglyphs, now we must ask—why is the king with baboons? As John and I wrote in The Ancient Egyptian Netherworld Books:

Baboons are a model of proper worship for the king, and are even said to have taught the

Egyptians how to worship the sun, such that the king himself “knows this mysterious

language that the eastern souls speak, they singing chatter for Re, so that he might rise

and that he might appear in glory in the horizon.”

In the Book of Adoring Re in the West (the Litany of Re), the same text that praises Re as the Great Cat, the sun god can appear as a baboon-headed mummy. The text to the simian solar manifestation is:

Praise to you, Re, high and mighty!

Jubilating Baboon, he of Wetchnet.

Khepri, correct of visible forms.

You are indeed the corpse of the Netherworldly Baboon.

(translation Darnell and Darnell, Ancient Egyptian Netherworld Books)

The sun god here becomes a baboon who praises himself. This makes sense, because Re is Khepri (depicted as a scarab and written with a scarab hieroglyph), who name means “to manifest, to transform.” The secret language of the baboons, the mystery of solar transformation—you too can be inducted into this knowledge in my upcoming live, remote class